On the occasion of the World Day of the Imprisoned Writer, the emblematic Ma Thida, Head of the International Committee for Writers in Prison, in a candid, in-depth conversation with PEN Greece’s Representative to the Committee for Writers in Prison, Lale Alatli.

World Day of the Imprisoned Writer, established by PEN International and observed on 15 November, reminds us that freedom of expression is a right that must be won anew every day through perseverance and collective solidarity. To mark this day, PEN Greece’s representative to the Committee for Writers in Prison, Lale Alatli, spoke with the emblematic Ma Thida, Chair of PEN International’s Committee for Writers in Prison.

At what point in your life did writing become, for you, an act of resistance?

Because censorship had been in place in my country four years before I was born, I was aware of the lack of freedom of expression from an early age, even before I fully understood its implications. My writing came from a desire to push the limits of what an ordinary person in society was allowed to say.

During your years in prison, what was the most important lesson you learned about yourself — and about the power of words?

During my time in prison, we were forbidden to read or write. But I soon realized that my urge to create, express, and shape my thoughts into words could not be silenced by any authority. I found ways to smuggle in books and scraps of material to write on. I managed to compose poems, essays, short reflections, and record important dates and memories. One essay—written in a style like language poetry LP—survived those years and is now studied by researchers, educators, and young writers. Prison taught me this: the power of words must be used in every circumstance. Listen to your inner voice. If you are meant to write, you can be a writer even behind bars.

How did you manage to preserve your creativity and your voice while living under such harsh restrictions and silence?

The desire to shape our own voice cannot be silenced – not by harsh conditions, nor by the authority of a prison. We only need to stay rue to ourselves and to our faith in creativity and literature. Freedom is not merely a matter of circumstance: it is often a matter of choice. The freedom to express and create can only be taken when we surrender it. I chose not to give it up. Even behind bars, I remained a writer – and a free person.

How has the situation for writers and journalists in Myanmar changed in recent years — if at all?

The situation for media freedom and freedom of expression is extremely precarious—one of the worst periods in the country’s history. Writers and journalists are increasingly targeted, and silencing these creative voices undermines not only political dissent but also cultural vitality, historical memory, and the public’s right to form opinions. The military junta tightly controls the flow of information, blocking social media platforms, imposing internet shutdowns, and shutting down or revoking the licenses of independent media outlets. This has created a climate of fear and widespread self-censorship among creative professionals.

A large number (around a hundred) of journalists and a dozen of writers have been arrested, detained, charged, and sentenced. Many independent media organizations have been pushed underground or forced to relocate abroad. Journalists and writers have fled, now working covertly or operating in exile in order to continue publishing and broadcasting. Article 505 (a) of the Penal Code and other defamation laws are used to criminalize incitement, false news, agitation, and undermining state stability.

But at the same time, there are underground or alternative literary expressions, such as collaborative digital platforms and special literary journals operating from abroad, as well as those from the country.

How important was the support of international organisations such as PEN for you, and what changes would you like to see in the global effort to protect writers at risk?

PEN’s support for my release played a crucial role in raising global awareness about the lack of freedom of expression in Myanmar. Their letter-writing campaign to me in prison, recognizing me as an honorary member of several PEN Centers, listing me as an Empty Chair case of the Writers in Prison Committee, and awarding me PEN America’s Freedom to Write Prize all helped protect me from severe neglect by prison authorities. Without this visibility—and given my deteriorating health—I might not have survived five and a half years of imprisonment.

From my experience, collaboration among international NGOs and civil society organizations is essential in protecting writers at risk. Additionally, both moral and legal support are important not only for the writers themselves, but also for their families. Without strong and compassionate support from family members, it becomes much harder to endure imprisonment. Finally, amplifying the voices of writers in prison—by sharing what they say, or publishing their work in the original language or in translation—can have a powerful impact in defending their right to freedom of expression.

Depending on the circumstances of each case, efforts such as traveling to the relevant countries, staging silent demonstrations in front of prisons where writers are held, and meeting with state authorities to advocate for their release (including handing out resolutions and statements regarding their cases) should also be revived – not only by PEN, but also by other local and international organizations.

As a woman writer and a doctor in a society with strong restrictions, what message would you like to send to young women who wish to express themselves freely?

A: Being a woman should never limit what we have the right to do. Even when we face strict constraints, our belief in freedom of expression can help us find ways and means to overcome them. So please hold on to your conviction and do not give up. But if you are uncertain about your own beliefs or your strength, it is better to pause and not act until you feel confident.

Do you believe that literature can truly transform societies that fear dissent and free expression?

Yes, literature can transform societies that fear dissent and free expression. As I often say, I was strangely happy when I received my prison sentence in 1993, because it gave me the chance to write my own prison memoir. I had always been inspired by the memoirs of independence leaders and freedom fighters, so I felt brave enough to dissent, speak out, and act freely against the military regime.

Although I was released in 1999, I could not publish my memoir until 2012, when censorship in my country began to ease. The book was well received by society, and many young people told me that they gained strength from reading it.

After the 2021 military coup attempt, many young people were arrested for peaceful protests. Some of them were inexperienced and became discouraged once imprisoned—they had joined demonstrations simply because they opposed the military dictatorship, but had not read or learned deeply about the struggle. In prison, youth leaders began smuggling in my memoir and my political essays, sharing them with those who had not read much before. When one of these youth leaders was later released, he told me that after reading my memoir, these young people became more active and determined to use their time in prison as a form of resistance. After reading my political essays, many of them joined in-prison protest activities led by the youth leaders.

Because of this experience, I am confident in saying that literature can truly transform societies.

What message would you like to share with Greek writers and readers about the value of free expression and solidarity among authors worldwide?

Freedom of expression is not only a fundamental right—it should be a way of life. Without it, we cannot truly claim our other basic human rights. Responsible and free expression strengthens our individual identity and encourages mutual respect for others. It also allows us to acknowledge the identity and freedom of those around us.

When practiced sincerely, freedom of expression helps us understand one another and creates a safer space for everyone, even when it may not seem so at first. Open expression can lead to disagreement or harsh arguments, but with responsibility and mutual respect, we can avoid harming each other’s dignity or freedom.

Solidarity among writers and creators around the world reinforces these values. By understanding others’ feelings through their words and work—shared openly yet respectfully—we gain deeper insight into the world and strengthen a culture of mutual respect. Ultimately, this helps protect our rights and ensures a safe environment to freely express them.

In your view, how can organisations like PEN International and its Writers in Prison Committee further strengthen their impact in supporting imprisoned or persecuted writers worldwide?

In an age of information overload, what people truly seek is not more data, but knowledge and wisdom. The role of a writer is therefore not only to inform society, but to interpret information, reveal deeper truths, and help us understand cultures and communities we have never lived in or experienced. Literature allows us to grasp the lives of people in a particular place and time, and ultimately leads to a more universal understanding of humanity. Knowledge becomes a blending of our own experiences with those of others, carried to us through literary works. For this reason, the efforts of PEN International and its Writers in Prison Committee are vital—not only in defending persecuted writers, but in protecting their voices and the important ideas they share with the world.

What we can do more are first by raising global awareness like using social media, public campaigns, and partnerships with journalists or cultural figures to tell the stories of individual writers who are silenced; second, by strengthening legal and emergency support including rapid legal aid, asylum pathways, and emergency funding in collaborations with international law firms or human rights groups; third, by increasing diplomatic pressure via the UN, foreign governments, and international courts like publishing detailed reports on violations of free expression in respective countries; and finally, by supporting writers in exile—through residencies, translation grants, or publishing opportunities. Protecting the writer also means protecting their words.

Having been both a beneficiary and now an advocate within the PEN network, what do you believe is the most powerful way for writers’ communities to show solidarity with those whose voices are being silenced?

Our existing approaches remain powerful: the empty-chair presentations, the recognition of the Day of the Imprisoned Writer on 15 November, organizing national events to honor persecuted writers, and reading or publishing their works. In addition, sharing UPR reports on the state of freedom of expression in each country, and using the annual resolutions and campaign manuals provided by PEN International and WiPC, all help strengthen these efforts. Together, these actions continue to be some of the most impactful tools we have.

Ma Thida (born 2 September 1966) is a Burmese surgeon, writer, human rights activist, and former prisoner of conscience. She has published under the pseudonym Suragamika, which means “brave traveler.” In Myanmar, Thida is known as a leading intellectual, with books that address the country’s political situation. She studied medicine in the early 1980s, earning a degree in surgery, and began writing at a young age. She has served as president of PEN Myanmar and is the Chair of the Writers in Prison Committee of PEN International.

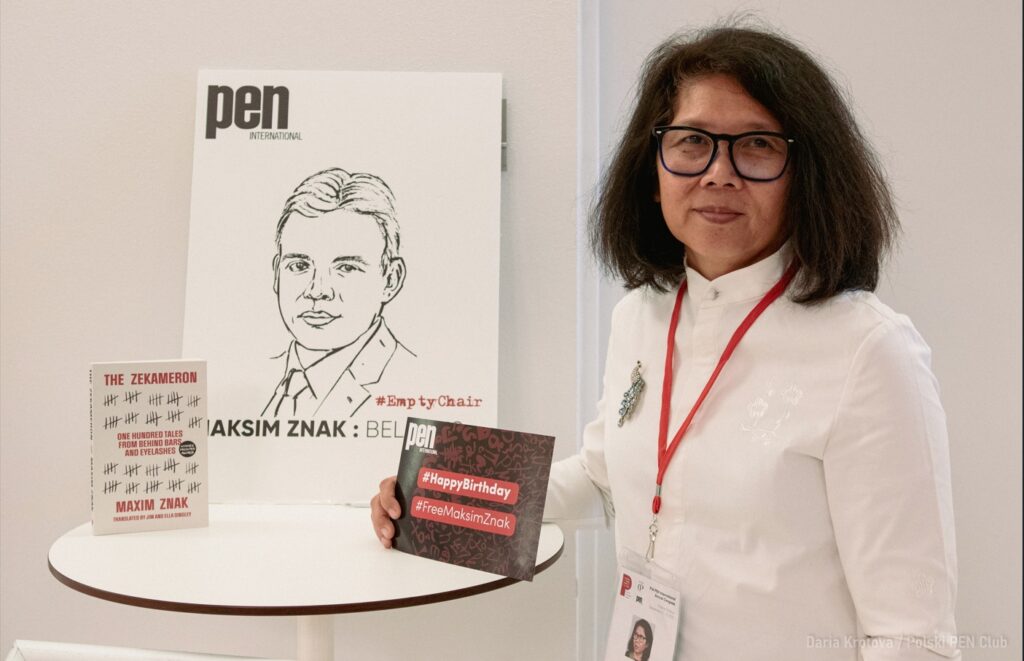

***Cover Photo: Credit: Daria Krotova

Lale Alatli, PEN Greece Representative to the Committee for Writers in Prison

Lale Alatlı was born in Istanbul in 1976. She studied in Istanbul, Florence and Komotini. She lives in Thessaloniki and works as a translator and interpreter of Greek, Italian and English. She has translated various literary works into Turkish. She writes short essays and poems. She is a member of Translators without Borders and volunteers in various environmental and animal welfare associations in Greece and Turkey.